To manage huge, highly detailed maps in a blocky game (a la Minecraft), the first bottleneck comes very early in development: the amount of blocks to deal with. This subject has been documented extensively, so I’m not going to spend too much time explaining it. If you are interested in procedural, blocky generation, you probably won’t learn anything new here. However, you should still watch the video below, as I’m presenting a few less talked about concepts I’m using for my project (nothing fancy or revolutionary, though!).

It’s pretty obvious that, even with the best specced machines out there, you can’t represent all blocks of the map at once. Let’s imagine a map that is 256 blocks long in all 3 axes. And let’s say one block is 1 meter long in all axes (this is roughly what a game like Minecraft uses). For procedurally generated blocky games, the appeal if very often the seemingly infinite exploration potential, huge and intricate worlds, etc.

Right off the bat, a 256 meters map doesn’t feel so impressive, does it? But if we were to generate all blocks individually, we would end up with 256 x 256 x 256 = 16 777 216 total blocks!

Our computers, our graphics cards, our CPUs are getting better and better, true, but hopefully you can imagine how approaching the problem from an individual block perspective isn’t viable. And even if our computers were so damn good that they could deal with this amount of blocks, is there a better way to deal with this problem, to increase the amount of data we can manage even further? (yes, obviously there is 🙂 )

Chunks

Sometimes called pages, chunks are simple ‘packs’ of adjacent blocks in 3D space. Instead of evaluating each and every block individually, we take a step back and work with large sections of the map.

Chunks are quite easy to understand, and naturally fit in our 3D, blocky world structure. Accessing a block now just requires an extra step: finding the chunk it is a part of first. This is usually done with some coordinates / indexing tricks. If my chunks are 100x100x100 blocks wide (and the origin of the world is {0, 0, 0}), the block at the 101x101x101 coordinates is part of the chunk {1, 1, 1}. Easy.

Some games use non-uniform sizes for chunks (I think Minecraft uses big ‘pillars’ of 16x16x256 blocks). For my project, I settled with 64x64x64 chunks. There are a few reasons for this, most of which will be explained in a future article about meshing 🙂 .

Chunks also fit well in a parallelized algorithm: because the data is already subdivided into discrete, independent sections (the chunks themselves), it’s pretty straightforward to send whatever generation / meshing is needed to background threads, per chunk.

Cells

Most maps tend to try to replicate an Earth-like, or rather planet-like look. In those maps, you have a mostly flat surface, with some ups (mountains) and downs (valleys) as well as some 3D structures (caves, tunnels, etc).

This is an opportunity for some optimisations. As mentioned above about chunks, some games have chunks that cover the full height of the map. In those cases, unless you come up with a way to split generation / meshing of these chunks into a ‘sub-chunk’ structure, you will have to generate and mesh the whole height of the map constantly. If the player is only passing through a region of the map, staying above the surface and never going down, you are wasting quite a bit of resources.

Instead, having multiple chunks subdividing the height of your map makes it easy to limit the generation where it is actually needed. In a future article about meshing those chunks, we will talk about how we want to only mesh what is actually visible to the player. Here, the approach is the same: only generate the chunks that are actually visible.

Not only does this speeds things up considerably, but it also gives you more freedom for the size of your maps: now that I know I can only load the necessary chunks, I could have maps with an infinite height!

One way to deal with this is to generate the 2D information of our map (the height) in a structure separate from the 3D chunks. I’ve called these objects ‘Cells’. Any time a 3D chunk is needed, I first need to make sure the Cell for the 2D location exists and has been generated.

Because Cells only care about 2D information, they are usually extremely fast to generate. Currently, in my project, a 64×64 cell takes an average of 130 microseconds to generate. So fast that I don’t even need to generate them in background threads.

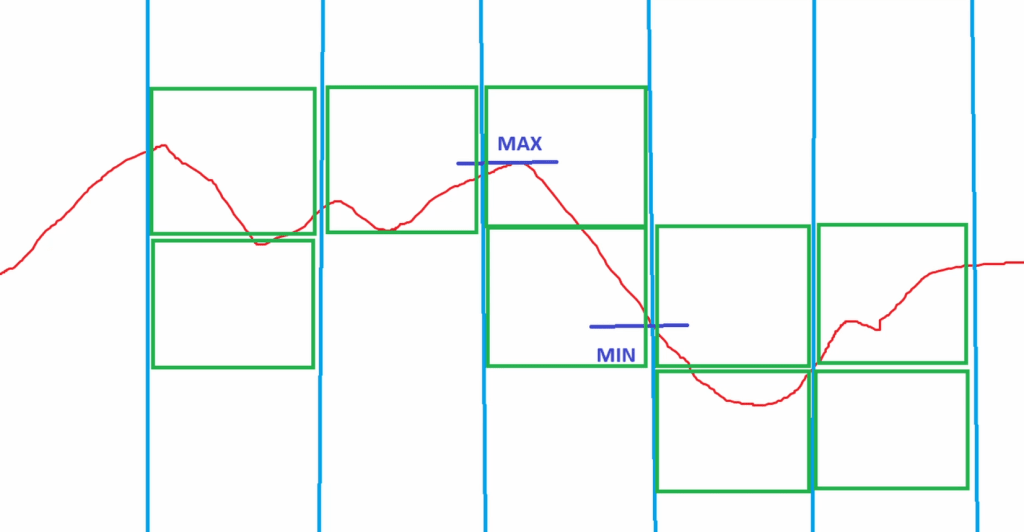

Out of this Cell generation, among all the useful information I’m getting, I use the min and max height to know the min and max 3D chunks that need to be generated. Pretty straightforward! Here is a less pretty image of what I’m talking about:

This is a side view of the map, for the sake of the example. The red line is the height (in blocks). The blue vertical lines represent the separation between the 2D cells. The green squares represent the chunks that have been detected as needing to be generated. This is all based on the min and max block heights that we find on each cell.

Of course, when we add 3D noises, caves generation, etc into the mix, things are a little bit more complicated (but not that much!).

Each chunk, during its generation, holds information about which of its 6 faces have at least one empty block (air). Using this simple information, we can know if we should generate the adjacent chunk or not. Imagine that our 3D chunk has a big hole in its bottom face (face facing down). After this chunk has been generated, we just need to add the bottom chunk to the list of new chunks to generate.

As generation progresses, all visible chunks are generated, and trigger the generation of their adjacent, visible chunks as well!

Resource Management

Even though Cells are almost instant to generate, Chunks tend to be slower, especially as you use more noises and more complex algorithms to define the block types that should be generated. Unless your maps are very simplistic, you will almost inevitably have to use background generation for those 3D chunks, to avoid freezing your game every time a new chunk needs to be generated.

As stated above already, chunks are mostly independent from each other so they fit this multihreading scenario very well. One complication in my project is one feature I’m really adamant about implementing: the ability to have multiple maps loaded at once (not only for servers, but for a few other gameplay reasons I will probably be developing in a (far) future article).

If you only ever have one map to deal with, and you implement multithreading for your chunk generation / meshing, you are done! Congrats! however, if you want multiple, concurrent maps, you will need to make sure your multithreading system is a global one, and not map-dependent.

Indeed, while you may have multiple maps running on your game, you still only have one computer! You can’t magically generate double, triple the amount of chunks.

I’m using a central threading pool, managed by what Unreal Engine calls a ‘GameInstance Subsystem’. A game instance subsystem exists for the whole duration of the game, it is completely independent from the level (map) that is currently loaded.

Using this subsystem, it’s pretty easy to balance the resources: all Map Managers (the actors managing a whole, independent map) simply submit their generation / meshing tasks to this central pool, instead of having an individual pool of their own.

Generation Priority

Whether you are supporting multiple concurrent maps or not, it is usually a good idea to be able to prioritize some chunk generation over others.

In the previous article (and its linked video), I presented the concept of ‘activators’: the activator objects are responsible for telling the map about which chunks need to be loaded (and generated).

In my project, a map may have many different activators, which are more or less relevant to the gameplay. The most important activator, obviously, is always the player’s: whenever the player moves and needs new chunks to be generated, we should prioritze those over the cosmetic-only activator at the other side of the map, that we can barely see.

But generation priority isn’t just tied to the activators: in the same previous article, I explained that to achieve really massive world, I had to implement Levels of Generation (LOG). Chunks immediately around the player are generated in their highest level, while chunks farther away get a lesser and lesser LOG value.

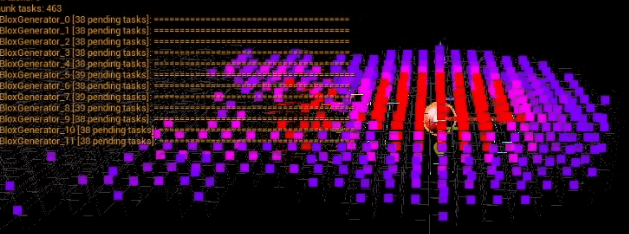

In the (shamefully low-res) picture above, taken directly from the embbeded video at the top of this article, the points represent chunk generation tasks, and their color represents these tasks priority value.

The redder a task is, the higher the priority. The player is represented by the big red sphere. As you can see, chunks with a higher LOG will get generated first.

You may even notice the trailing chunk tasks on the left: the player just moved (toward the right) and we can see the chunks on the edges were still not generated, because the ones in the center (closer to the player) were more important.

Continuous Background Generation

All of these tricks, all of the data structures presented during this article mainly focus about ‘optimisation’ and efficiency. Hopefully by now you understood that these things are helping us achieve bigger worlds, faster!

However, it is unlikely that your game will be constantly under full stress, and the player will not keep moving around without ever stopping to take a break. In a game like Minecraft, a player may chill for hours (or even days) in the same area, building a cool base, mining the same cave, etc. During this whole time, the same chunks will be loaded, and very few new chunks will be required to be generated.

So, when you have resources available, why not use them?

This same player will probably want to eventually start exploring in another direction. They may dig too far and discover another extensive network of caves spreading way past the current loaded map.

I have added an option (disabled by default) on maps, called the Continuous Background Generation. When the game is mostly idle (generation and meshing wise), the map may decide to keep generating new chunks (adjacent to the already generated chunks). This means that when the player finally decides to explore and extend the map bounds, the chunks will already be generated, and will load almost instantly.

Furthermore, this background generation always triggers the highest Level of Generation, meaning that we will not be ‘wasting’ resources having to generate greater and greater LOGs as the player approaches the chunk.

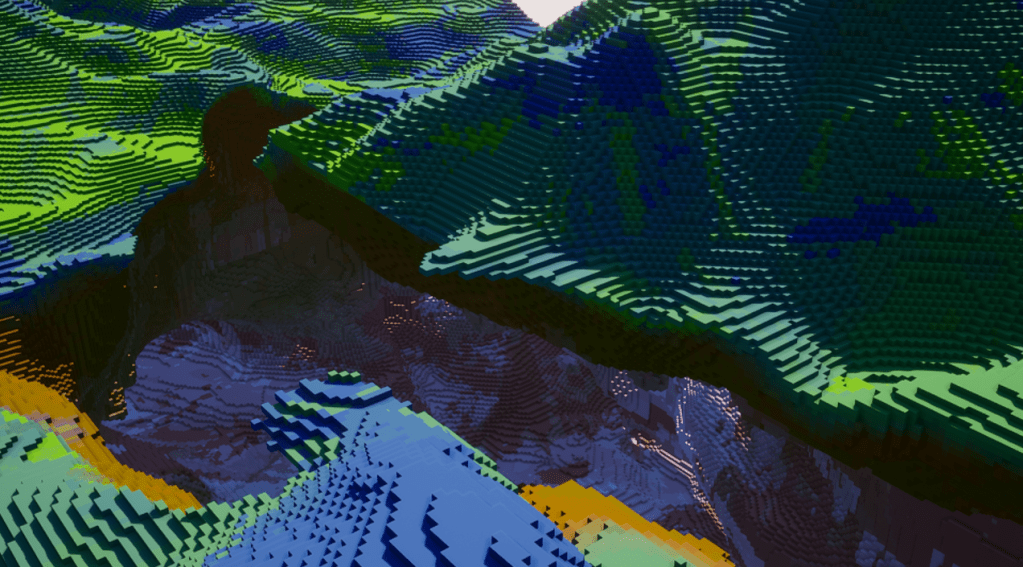

You can see the continuous background generation in action in the video (see the top of the article). I think it’s pretty cool!

Conclusion

In the video, I talk about a couple more concepts (the Region data structure), but they will have a greater importance for future articles, so I’m going to stop here!

In the next one, we will be taking a closer look at replicating actors, and how to deal with multiple concurrent maps in the server 🙂

Leave a comment