Programming with replication / networking in mind from the beginning is important, especially as you often build the very fundamental concepts of your project during this initial stage. It’s just too easy to be lazy (like I did a few years back, when first starting this project) and tell yourself you are going to ‘add multiplayer’ later.

This just isn’t how it works.

Our chunk-based world (read previous article) is intended to support multiplayer, and notably with multiple concurrent maps, with some players in map A, some other players in map B, and why not some AI (non-human) in map C. This means we need to build our systems so they work both in standalone (solo play) and multiplayer (whether listen server of dedicated server).

Unreal Engine is built around a server-client model, where the server is authoritative. I won’t talk about generic Unreal networking stuff, as many others have done it already. A quick search on the Internet should give you plenty of results and tutorials 🙂 .

Here is a quick video, if you prefer images over text!

Replication Groups

First, when you have a potential for huge levels and many players that need to interact with the world and with each other, replication becomes a high priority on the list of things to optimise.

Indeed, we can’t afford to replicate thousands upon thousands of actors and variables, all the time.

Even though the worlds might be huge, usually players only care and interact about their immediate surroundings. If a tree falls in the forest behind the player, do we really need to replicate this event? No, we will only replicate the tree, already on the ground, when the player approaches close enough so they can see it.

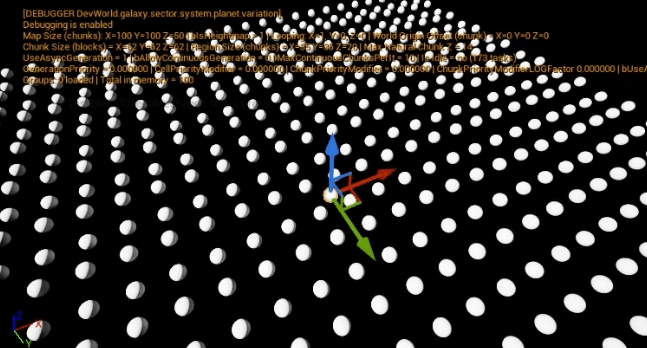

This brings us to the first aspect of our replication system: map replication groups, which are spatial subdivisions of the 3D space. Sounds like chunks? They are essentially chunks! They don’t draw any mesh, nor do they contain any data about the blocks, but they are 3D volumes placed at regular intervals in the map.

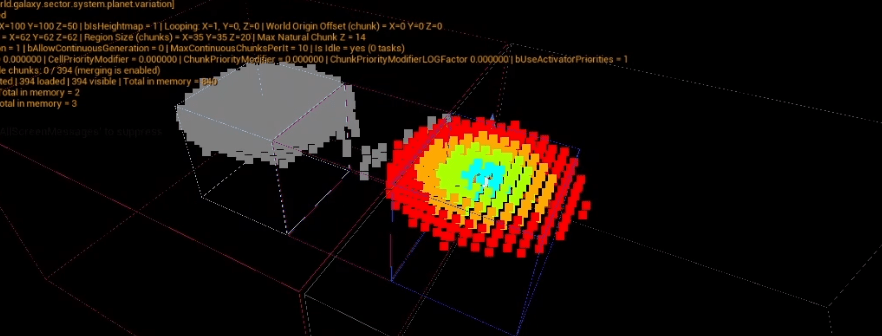

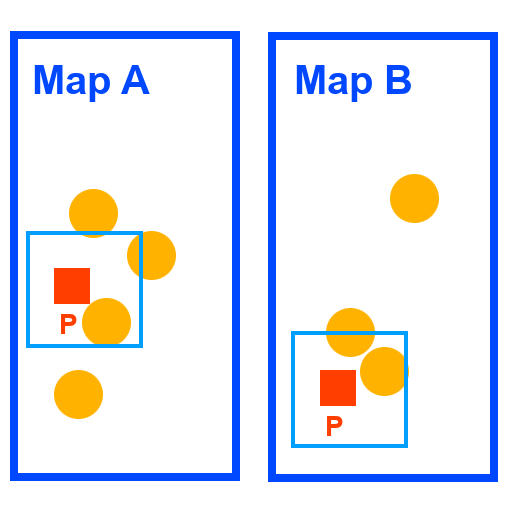

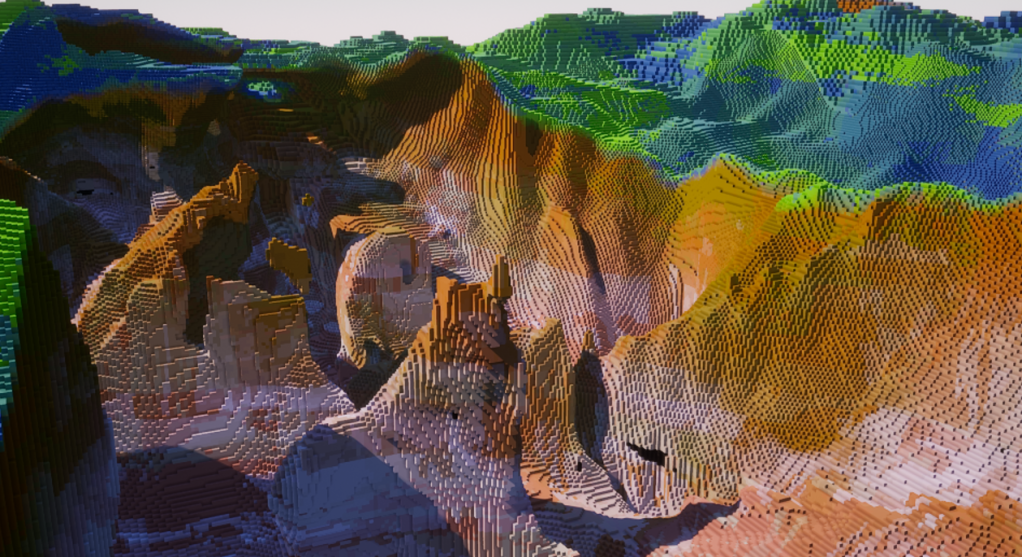

The above screengrab shows 3 things:

- The grey and colored squares are the chunks (holding the block data),

- the 3 boxes around them (center of the image) are the map replication groups,

- the 2 bigger boxes are chunk regions.

Chunk regions were briefly introduced in the previous video and they are not related to replication, so I won’t talk about them here. The only useful thing to know is that they are not used for replication: the map replication groups, as you can see, are a completly separate structure, and are smaller.

I’m using the Iris replication system in Unreal, which supports replication groups natively. This means that the only thing we need to do is add the player connections to the groups that they need to replicate.

The idea is simple: whenever a player enters a new map group bounds, its connection gets added to this group. If we make sure any replicated actor follows the same principle, all actors in this group will be replicated, and all players in this group will also see each other.

All other actors, in other map groups, are not replicated to this particular player connection.

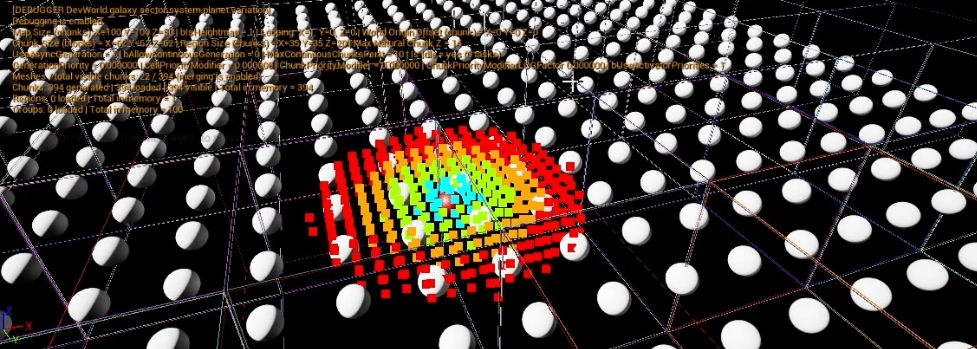

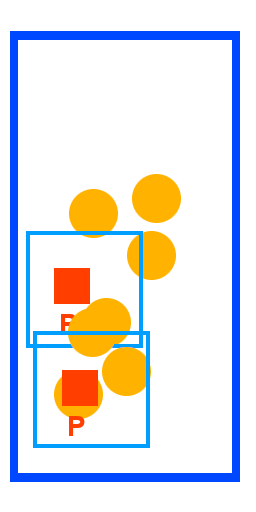

The above is a view from the server. All white spheres are replicated actors (notice the colored boxes: the map replication groups).

Here is the what happens on the client:

As you can see, the client only gets a few actors replicated, the ones that are around their pawn.

Extra Safety Buffer

We’re not just adding the player to one replication group at a time. Because a player may move erratically, we need an extra buffer of replication groups around the one the player pawn is actually located in.

Imagine the player is exactly at the border between 2 replication groups: without this buffer, all actors of both groups would pop in and out of existence every time the player crosses the border.

This is why in the previous screenshot, you may notice that we get more replicated actors than expected, if you compare with the replication groups size from the previous image.

This does means we’re adding the player to (max) 27 replication groups instead of 1 (+1 in all directions, including diagonals), so it’s not without cost (reminder: ALL actors inside a replication group will get replicated). This is why it is key to pick a sensible size (in chunks) for your replication groups. Too small and not enough actors will get replicated, too big and the extra cost will become a bottleneck.

My current replication group size is 10x10x10 chunks, but I will probably adjust this when I have more data to test with (big white spheres scattered on the map isn’t a good example!).

Delayed Replicated Groups Removal

Again, as the player can move unpredictably, we don’t want to remove them from a replication group as soon as they exit one. If we did, and the player changes their mind, backtracking to their previous position, then we will have to re-replicate all the actors that we just stopped replicating.

The solution is straightforward: just have a delay between the time the player leaves a group and the time we actually remove it from this group. If, during this time, the player re-enters the group, simply cancel the removal!

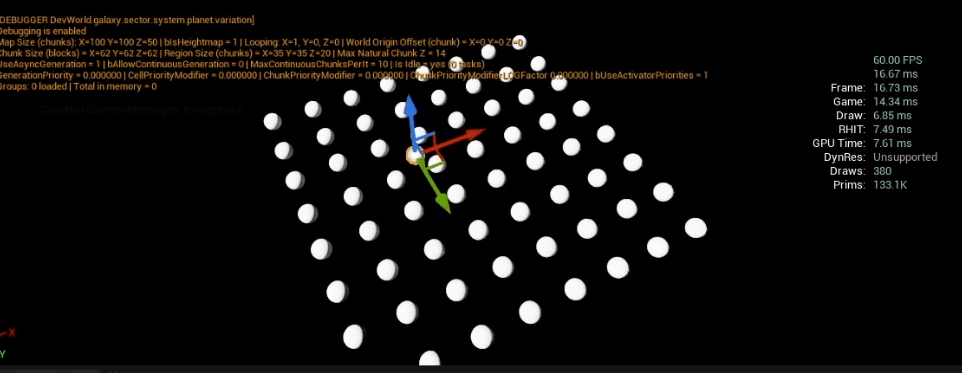

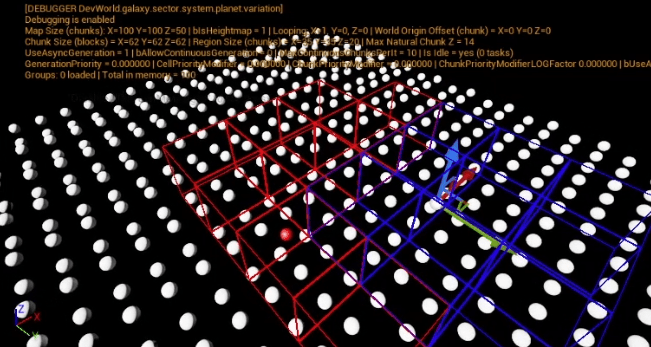

In the above picture, the blue boxes are the active replication groups, the one the player is considered to be ‘in range’ (notice that, as explained above, this is not just 1 group, we have an extra buffer of groups around the central one).

The red boxes are replication groups that the player was in range of previously, but they are pending removal. They are still active, and are still replicating their actors to the player, but unless the player moves in their range again, after the removal timer is over, these groups will stop replicating their actors (to this particular player’s connection).

Note: in the screenshot, we can see all white spheres / replicated actors, even the ones not in any of the player’s replication groups, but this is because this is a view from the server, so you can see the boxes. This is because the client actually doesn’t know anything about replication groups. Only the server manages them. The client simply received replicated actors, or not.

Concurrent Maps

There is something I haven’t told you yet about replication groups: we have more than just the spatial groups. Indeed, we also have a ‘parent’ group: the ‘map’ group.

Unreal Engine doesn’t allow you to load multiple Unreal levels concurrently. If we want our game to support multiple maps loaded at the same time, with clients scattered across them, we need a simple way to completely switch on or off replication of whole worlds for specific player connections.

We’re using the exact same structure: each map has its own replication group. The spatial replication groups that we saw above are just a smaller, finer subdivision of the space.

Any time an actor is spawned on map A, it has to be added to map A replication group. This means that only players currently in map A will potentially replicate it. All other players will never even be considered for this actor.

In the (ugly) image above, we have 2 maps (A and B). Each map currently has one player (P). The orange circles are actors on the server, that potentially need to be replicated.

The light blue squares around each player represent their active replication groups range.

Now in reality, what is happening in the Unreal level is that these 2 maps might overlap each other spatially. The clients only replicate the actors that are part of the map they are currently in, so visually they will only see their map. But from the server perspective, everything will be on top of each other.

A bit of a mess, right? This is why having proper separation via map groups is so important.

Even though actors and players might be close to each other in the 3D space, even potentially overlapping, what really matters is the map they are in.

One major caveat, obviously, is that this approach will prevent you from using many built-in features of Unreal Engine: physics, traces, etc (unless you want to feel the pain of managing complex channels for collision, etc). In my project, this was already a given: for reasons mainly unrelated to replication or even concurrent maps, writing my own physics and collision system is just more efficient (blocky games allow for nice shortcuts).

Managing Visibility aka ‘The Listen Server Problem’

Since the clients only get replicated the actors that are actually relevant to them, they will never show undesired actors that shouldn’t be here, like a player pawn on a different map for example.

Unfortunately, we can’t say the same about the listen server host. Like a dedicated server, a listen host is a server. This means the host does not replicate actors to itself: all actors exist for the host, all the time. Looking at the previous image, you might realise why this is an issue.

The listen host is a server, true, but it is also a player. And like the other players, it needs to only see what’s relevant to it. If the host is on map A, it should not be seeing the actors (and client pawns) of map B.

The solution is simple, but it requires some special treatment and code exclusive to the listen host. If you don’t plan on supporting player hosted games, that simplify things a bit.

In my project, all actors that can be placed in the world have a ‘locator’ component. This component is tied to one map (and only one). This can be used to identify on which map this actors currently is.

Whenever such a locator component is ‘linked’ or ‘unlinked’ from a map, we check whether the player is the listen host. If it is, we need to override the actor visibility (visible if added to the map the listen host is in, invisible if on a different map). There are a few places where we need to make such a check, they should be obvious when you playtest.

The one issue is that Unreal replicates actor visibilty. So if the listen host on map A sets an actor of map B invisible (because it should not be seeing it), then all clients on map B will see the actor suddenly disappear. Not cool! The trick is, instead of setting the actor visibility, the listen server can set the actor root component visibility (HiddenInGame in Unreal), which isn’t replicated.

This trick has one main drawback: if you are manipulating the HiddenInGame of your component for gameplay reasons (unrelated to replication), then this fix about listen server will interfere with it. Also, keep in mind that to ensure the fix is working, we need the HiddenInGame edit to be applied to all children components (bPropagateToChildren = true), so this is not just affecting the root component. For my project, I’m fine with this issue.

Chunk-based visibility

Even without talking about replication or listen server annoyances, actors spawned on the map should not always be visible. While they are not directly tied to the chunk data (the blocks the map is made of), they are still, in a sense, part of the chunk they are located in (even the dynamic, moving actors).

As I was writing previously, all actors have a ‘locator’ component. This locator component knows about the block and chunk coordinates of the actor (simple conversion of Unreal units to map units).

Knowing that, I implemented a delegate system, where chunks broadcast their visibility changes: when a chunk becomes visible or invisible, it tells all its ‘listeners’ about it. Locator components automatically start and stop listening to chunks as the actor moves, making this completely automated.

If you have extremely large actors (spaning multiple chunks), you will have issues with visiblity popping in and out at unexpected times. This is because the locator component only cares about the actor position.

For very large actors, you instead need to consider the actor bounds. It is slightly more expensive, but it is only needed on very few actors. Most regular-sized ones will never exhibit this issue.

In the above, the green mush of pixels around the big sphere is actually all the chunks the actors is overlapping with. Now, compared to the previous animation, the actor only gets hidden when none of the overlapping chunks are in range anymore.

Conclusion

Despite everything that has been mentioned here, remember that Unreal Engine provides other native functionalities that help optimising networking and replication (replication priority, relevancy, dormancy, etc). I am also using these features, on top of what I’ve presented here, I just didn’t think it would be relevant to explain them when there is so much documentation available already.

Replication is an ongoing process, and any new feature added needs to be ‘networkified’, if relevant. But this base, to me, was very important to have right at the start, before moving on to other gameplay aspects.

I will be posting more about replication in the future. The next article, while not directly about networking, will touch on it: it’s about looping map coordinates and world origin offset! Stay tuned.

Leave a comment